How do we honor a story? And what is ethical storytelling and why does it matter?

The Story of a Syrian Refugee

This last weekend I gathered with my book club to eat Syrian food and learn about the crisis there.

I spent the meal talking to our gracious cook, Shaveen, who made us some of her favorite food (but not her MOST favorite, she confessed to me later). We chatted about having sons of a similar age, moving far from home, and her favorite sites in Syria.

Later, she shared her story as a refugee with our group. It wasn’t finely tuned. It was the good, bad, ugly and random, all thrown together. She shared a linear human story, not a professionally woven one. For all of us, it was better that way.

Near the beginning of the story, when bombs were falling, her brother-in-law was shot dead, and stomachs and limbs were found in the street, Shaveen would pause. Her silent tears wrecked us. A woman hosting the event, gently came behind her, laying a comforting hand on Shaveen’s shoulder. Shaveen pulled herself together, only to share about fleeing, getting to Turkey, her fears, and the prejudices she experienced. And then again, she would choke up and cry.

I have never lived through anything like Shaveen has. Because of my medical experiences, I related when she told us, “I wasn’t sure if this would be the day I’d die.” This is the type of trauma that is sure to bring on PTSD. But we have that in common for very different reasons. I don’t have her story–I haven’t had to flee my home, fear for my whole family, be questioned every few blocks, nor watch people go off to get murdered. Her refugee story has so many similarities to the one we were reading as a book club. I never considered how I might want to stay and wait it out. Until that becomes a death sentence.

Shaveen was a raw representation of war, a much larger social issue than herself. Even so, her story is her own. It doesn’t belong to us. It matters because she matters. And she deserves to do with it what she wants.

Using Storytellers For Their Stories

Watching Shaveen cry brought up feelings.

I love things like this. They are familiar to me and effective. Stories must be shared. These are the inciting moments of “It Became REAL,” or Phase One of Rising Up (you can grab the guide here or below).

They are also a way the storyteller relives their trauma, which can be healthy or unhealthy. It can be very damaging without previous healing support and care, such as with therapy or long-term pastoral care. Sometimes people never get to a place where they can share their stories without it bringing them back into deep fear and darkness.

I have frequently seen open raw stories + events mixed. I have been the one who would sponsor it, not always paying the storyteller/speaker. Or realizing that the person who was sharing their story wasn’t ready. I am guilty of using wounded people’s stories to produce advocates or get new donors. Even now, I am unsure of using this event to even talk about ethical storytelling, even though there are enough characteristics behind the scenes of this blog post that make me think it is okay. (Also, this isn’t commentary on the hosts of this event!)

Rather, I wish I had more wisdom as a young activist leader. A few months ago I wrote a piece about doing anti-trafficking work differently. Ethical storytelling is another one of these areas I’ve grown in, what I now try to practice as I connect everyday people with social issues.

Ethical Storytelling

These days, we have a lot of feedback on what works and doesn’t. This feedback either wasn’t available to us before, or more likely, we hadn’t known we should ask for it. These are the relics of individualism, white savoirism, and supremacy. It has just been the way many of us were trained by our dominant culture to do charity work. In college I began studying the ways we would barge into cultures and think we had answers, but too often we didn’t. We just domineered and assumed our ways were best. Unintentional as the harm was, my generation of advocates and activists are finding they have to repent of this, turning to do good better.

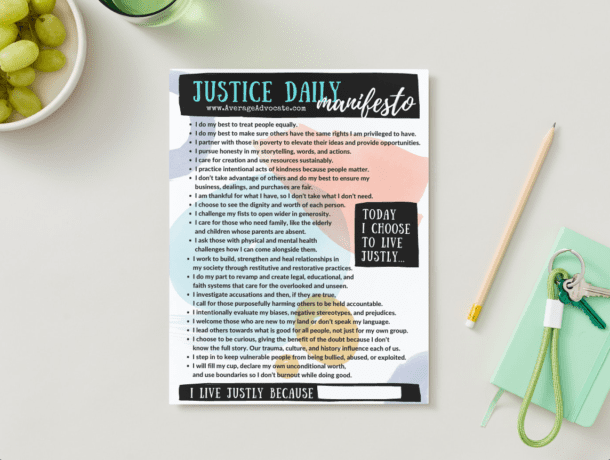

One of many areas our helping has hurt has been in our storytelling. But the good news is that we can connect future activists and donors with causes we need them to support in a more ethical way. This is what we call ethical storytelling. Because stories matter, and the people who lived the stories matter, we care for the storyteller and listen to their needs first.

The Storyteller’s Waves of Trauma

Having lived through complex trauma myself, I see a public/private pattern of healing. At times to heal, I need to share parts of my story out-loud. At times I must go back and process a different layer in private. These are waves. It isn’t much of a process.

This is confusing to those of us who haven’t lived through the trauma. For example, many of my White friends often feel confused by what they hear from the BIPOC community (myself included). We hear, “You don’t know what we’ve been through! Listen to us and our stories!” and then, sometimes when we are asking to listen and learn, we are told, “Why are you expecting me to relive my trauma for you? The weight of education can’t be on People of Color! Educate yourself!” These seemingly mixed messages can come from trauma responses, where one person is in a season of quietly healing (hopefully) and the next person is needing to share their experience. It is the waves.

Whether someone was trafficked, fostered, has lupus, lost babies, is a survivor of domestic abuse, has suffered as a minority, or is a refugee–these situations are traumatic to live through. Trauma automatically affects a person’s whole being, including their body’s response, their mental health, and even their spiritual beliefs must be reconciled. We can’t really know where someone is in their process.

But even knowing this is happening among any storytellers who have lived-experienced or are survivors can help us a lot. It helps us be more gentle, more aware, more considerate of their needs.

When We Fail and Don’t Meet Needs

A couple years ago, I helped conduct an interview with a person I already knew. Based on the decision makers for their hiring, I knew that if they shared their story as a survivor it would win them major points. They’d likely get the job, as their background was very helpful for running this particular organization. I asked them to share. They did. The predictable response also happened–they got the job. But, it wasn’t until later that I learned how frazzled and affected they were by going from sharing a most raw and personal part of their life to being question about qualifications immediately afterwards.

This is an example where I failed at ethical storytelling. The root of ethical storytelling is seeing the person and walking alongside them to meet their needs. And as there is no real formula for knowing what someone’s needs are, or how to walk alongside them well, “failure” is inevitable. But so is growth and reconciliation. We have the chance to apologize when we’ve done it poorly. We learn to be more considerate, asking or showing the people their worth.

10 Questions to Help Us Practice Ethical Storytelling

Sometimes I’ve found people really want their stories to be told. Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes we are responsible for sharing it. Othertimes, like in Shaveen’s case, she was the storyteller herself. (Until I retold it.) Here are things I am learning and questions to ask to be more ethical in my storytelling:

- Have you asked before sharing someone’s personal story? Or at least see if it is public or if someone else got permission to share.

- If you don’t have permission to share someone else’s personal story, should you even share it? Would it be using them to share it?

- Can you help a person remain anonymous if you are using their experience or your experience with them to talk about a social issue?

- What is your motivation in sharing? Is it for the “greater good,” at their expense? Is it to make you look good? (This is sometimes called virtue-signaling)

- Can you ask them how they would like you to share their stories? If that isn’t possible, if you were them, how would you want to be shared about?

- In the story or images, do you look like the hero of the story? How can you present in a way that makes them the hero of the story instead of you?

- When I was a missionary, I would present as the hero of the story. In retrospect I could have turned things around to share stories in a way that wasn’t so white-saviorish. That would have actually been easier, especially when I was the main one learning among the cultures where I was!

- When sharing stories or about a cause, can you recognize if you and the people you are sharing about aren’t actually equal? Can you see where you might have power or privilege? How can you use that for good in a way that honors their story?

- Are you being honest in what you say?

- Are you double-checking your facts? Are they exaggerations?

- Are you focusing on only negative stereotypes or drama?

- What are other truths you can unveil through your stories?

- For example, are all your stories on Africa lumping a massive continent together or are you giving dignity to the extremely different regions? Are your stories just sad about poverty or HIV? Do they include other things that are also true, such as areas where there is thriving, the many who are succeeding, those who are joyful, those you can learn from?

- This is something I am just learning how to do. I find it a challenge, as I am creating awareness about things that are negative. But when I go back and read what I write, I realize sometimes I can add in other things to bring a little more balance, tilting away from just negative stereotypes.

- Does the storyteller know you value them? How can you show them that they have worth?

- Can you pay them? Even if they aren’t expecting it?

- Can you ask them try to honestly evaluate if retelling their story will be too much for them?

- Do they have supports in place? Have they gone through a season of healing?

- How would they like you to rally around them if it is difficult?

- Can you connect with them outside of the event? Remind them you see them, that they are more than their trauma story?

- Most importantly to wrap it up: Are you presenting them with dignity?

What are your thoughts or ideas to practice ethical storytelling?

Tools to Learn More About Ethical Storytelling

There are many books about how to do good better, so many leaders to learn from! From When Helping Hurts (a classic) to the Race-Wise Family, there are never-ending books. Even just listening to stories, like the one we are reading with our book club, The Beekeeper of Aleppo, we can examine how master storyteller, Christy Lefteri managed to pull us through an eye-opening traumatic story in a way that didn’t traumatize us. Instead, it was beautiful and hopeful, not too heavy. We could relate, easily putting ourselves in the main character’s shoes.

Two things that have helped me with ethical storytelling in particular are these:

- Kindred Exchange’s Podcast (there is a section on ethical storytelling. They also have a course)

- Trauma-informed writing training (as writing is often story-telling, this was a blast of really great content!)

As everyday advocates, how we tell stories matters, which is why we can work towards ethical storytelling. How we honor the storyteller also matters. When connecting people with a cause, we are giving a face to the cause. So let us give dignity to the storyteller and honor where they are in their waves.

“Love each other with genuine affection, and take delight in honoring each other.”

Romans 12:10 NLT