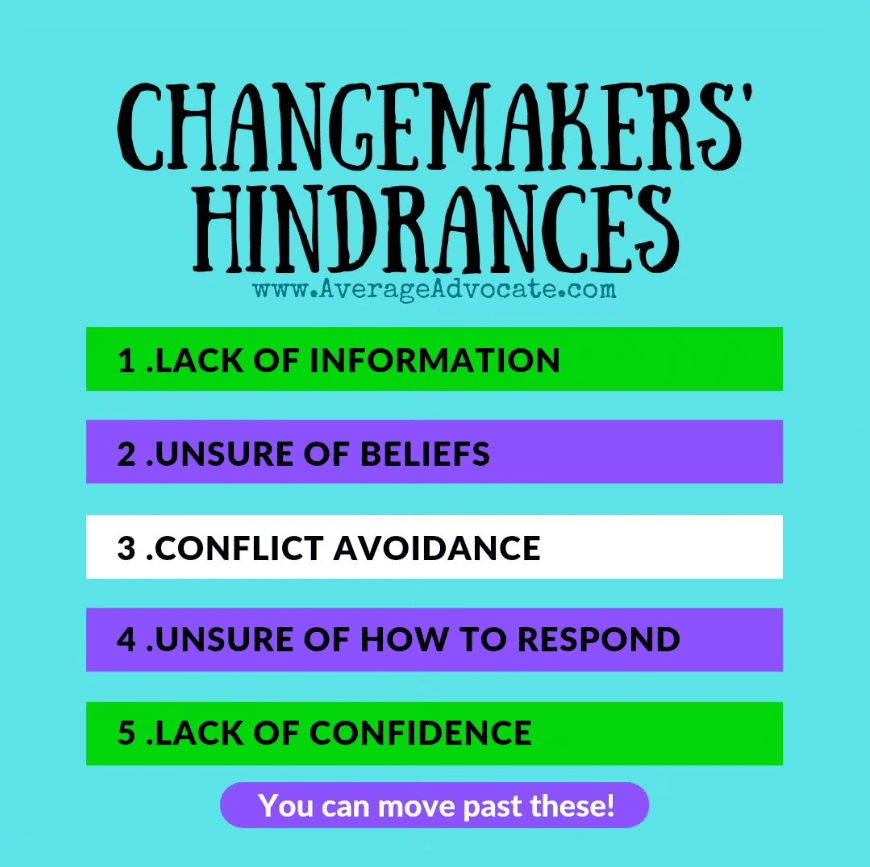

I’ve heard it over and over again, that getting involved in social issues is just too much. I get it. There is a black hole of needs–another famine, another sick friend, and then the news is a constant drone of everything depressing. It is overwhelming. That is why I am going to go over the five major hindrances that keep you from making a difference.

Over the last few years, especially in the middle of COVID-19, when the #BlackLivesMatter movement gained traction, I’ve been challenged to honestly evaluate the racism that still exists in our country–and in me as a White person. To help you understand these hindrances, I’m going to demonstrate how they have shown up in my own life in the context of understanding and getting involved in the social issue of racism.

1.) Lack of info

To start, there is trying to understand what’s going on in the first place. Finding facts isn’t always easy, especially with biases on every side.

As horrific as it is, George Floyd’s murder empowered many of us to see the truth that violent, and then systemic racism still is a huge issue in the United States. You know what finding information is like. One person says this. Another that. Fox News swings the story one way, and MSN the other. But seeing George Floyd murdered on video made it real for many White people as it couldn’t be explained by biased news reports. On the other hand, I spent more hours that I could afford to find unbiased information on Breonna Taylor’s murder. As I don’t have a personal stake in understanding murders in general, I had to push into it on the principle it was worth my time, despite every other thing clamoring for my attention. Why did I choose to do so? Mostly because I claim to be an average advocate. I had to put my time to back the identity I have chosen for myself. Only after I committed that time, could I feel empathy and care.

A common refrain from White people has been, “is racism really that bad?” Our lack of information and lack of interest in seeking information keeps us from getting involved in anti-racist efforts.

We give meaning to social issues the more personal they are to us. So, unless we are experiencing it ourselves, or close to people who are experiencing the social problem (like racism), it is unlikely it will feel real to us. But that leaves us with a need to have enough information about the problem to believe it is a worthy problem to care about. The whole hindrance–lack of information, is part of the first first Phase of Rising Up–“It Became Real.” You can learn more about it in the free downloadable guide at the top of this page.

When has a lack of information hindered you from getting involved in a social issue?

2.) Not knowing what we believe

Once you have information about the social issue, you actually have to know what you believe about it! We can usually agree that some things–like mass murders–are despicable. But the context is everything. Some people believe abortion is mass murder. Others believe war is. What do you believe mass murder is?

In the case of racism, I already had a strong belief. My worldview as a follower of Jesus impresses on us the equal value of all humans. Although I delved into more scriptures about culture, diversity, and race as I continue work to dismantle my racism, I overall knew what I believed (Here is an example). In other social issues, though, I don’t always share the popular belief, or my belief might be less black-and-white and more nucanced. There are some I am still unsure about and regularly experience internal tension as I am unsure where I stand.

You have to be confident on where you stand to make a difference. This Spectrum of Belief graph might help you as you evaluate your own beliefs.

3.) Wanting to avoid conflict

Then we are hindered by feeling as though we must manage the opinions of everyone around us. We worry about saying the wrong thing in our good intentions, being canceled, causing a scene, or being bullied when we are really trying to have a safe dialogue. It is exhausting. We aren’t out to offend people, after all. Better to not touch it, right?

For example, it might be trendy to say you’re anti-racist, but actually practicing it is much more difficult. It means listening to others who have hurt and trauma in their backgrounds. It means often feeling accused when you don’t see the context. We often have to humble ourselves, say sorry, even when we don’t fully understand why. Then there are the White people you might know who don’t value being anti-racist. Defensive, they might push back against any commentary you have on the subject, even if not directed at them personally. Alternatively, I’ve seen relationships deteriorate, not feeling like there is a space to talk about something so important and foundational to one party, while the other side doesn’t necessarily view it as a vital discussion piece, wanting to avoid it.

I often feel tension trying to figure out which types of things I can say about any social issues without being pushed away by my community. There is a very real fear here. In someone’s eyes, you’re probably doing advocacy wrong. I know for myself, I want to love people better, so I advocate. I don’t want to cause conflict. But sometimes it happens, even when I say things I don’t think will cause conflict.

On a different social issue–the American immigration system–I’ve had people upset at me and unwilling to engage in conversation because they disagree with me (which I expect to a degree). But I’ve also had someone get angry at me for talking about how to have conflict-free discussions on immigration. They weren’t angry because they are against it–but the opposite! They were mad that no one took their immigration experience seriously and therefore felt like Americans didn’t deserve a chance to change their ways and begin caring about the problem. Let’s just say I found that surprising!

Point being, avoiding conflict is a primary reason we avoid doing things about justice-issues. We have to decide that being a peacemaker sometimes doesn’t mean keeping the peace. (See more on peacemaking here.)

4.) Not knowing how to respond

Once we understand the problem, know where we stand, and are willing to find ourselves in challenging settings–what can we even do about the issues at hand? And of our options for action, what is good or effective? What do we have bandwidth for?

Going back to racism, sometimes the advice from the BIPOC community can be contradictory and confusing. Knowing who should be our guides isn’t always clear (although I’ll have recommendations I trust so feel free to ask)! Being allies in environments where we live within the brokenness vs. knowing about it far off (like is the case with racism), is a different type of hard work. It doesn’t take a break–you can’t just get on a plane and leave the problem behind. Being anti-racist requires us to frequently reassess our words and actions. We also have to get deep into how we are influencing systems where racism can thrive. We can continue being purposeful by asking people what they need, learning from them, their stories, and viewing ourselves as partners (not saviors) to walk a path towards restoration together.

However. . . we only have so much capacity to do this, let alone do this for more than one thing we care about at the same time! This is why I always go back to phases three (Movement), phase four (Invested), and phase five (Intentional) in the Phases of Rising Up, as they equip us in these areas. But to start, these three questions to know what to do with needs might help us with our limited bandwidth!

5.) Lack of confidence

The last hindrance is about our confidence. Our beliefs and mindsets about who we are always play a part. We can feel like we won’t be able to do it the best way, believe we are failures, become cynical, weary or burned out. It doesn’t seem worth it. Ultimately, we question whether we even have the power to make a difference.

When it comes to being anti-racist, it has been a long journey and I am still not there (nor will probably ever be). However, I have been learning and practicing activism for a long time (nearly twenty years!). I have found that I would flip-flop between being overly confident, because I knew what I stood for and had experience, to being humbled. And then, from there sometimes I would lose all confidence and feel pointless and unqualified to speak about racism. Recently, I wrote a short post about impostor syndrome for activists, and this was at the root. In addition, this post about comparison might help you if comparison is keeping you from having confidence to move forward making a difference.

Now that I went into details with examples of these five major areas of hindrance its obvious why we are overwhelmed! We might not like human trafficking or famine, but trying to move past these three FREAKIN’ HUGE hindrances that overwhelm us is no joke.

Overcoming Hindrances

Until then, your challenge this week is to spend five minutes in reflection. Consider these five areas of hindrance.

To help you reflect:

- Open a note on your phone

- Pull out a journal

- Talk about it with a loved one

- Stroke your chin while mulling over this on a drive

Here are three questions to help you reflect:

- Which have you or do you experience?

- What do they make you feel?

- What beliefs do you have that might hinder you?

Let me remind you that you aren’t alone. We are all experiencing these hindrances. Even the people who “are good at advocacy” still deal with the insane overwhelm. Keep sticking around, I promise to help you through these five hindrances.